What can Big Data reveal about our music identities:

Lessons in music theory from the Spotify School of the Arts

Lessons in music theory from the Spotify School of the Arts

There is a distinct moment at the end of a music festival when the realisation kicks in: ‘This is it.’ A potent mix of relief and music-induced euphoria, it is a fitting end to the night. Next, you find yourself propelled forward by a swarm of festival goers, leaving your brain to adequately catalogue the festival’s highlights: from acts with an overpowering stage presence who perfectly encapsulated the vibe of the show to anticlimactic favourites whose magic sadly doesn’t translate to stadium events. The rest is a blur. You make a mental note to update your Spotify playlist accordingly.

Back at the friends’ barbecue, the host asks you to contribute a song to the evening’s playlist. In a true Eurovision homage, each visitor must nominate a track emblematic of their homeland. Suffice to say, the choice reveals more about the individual than their homeland.

A drink and a half later, the host enthusiastically shares this eclectic music creation via a Spotify’s group playlist, and you are astounded by the amount of defining summer memories you’ve just fed an algorithm. This juggernaut of big data clearly holds a near perfect insight into your whimsical behaviours, concert trails, social interactions and listening routines. Possibly even your coping mechanisms inferred from that guilty pleasure soundtrack.

The questions thus arise: can this Musical Oracle hold a mirror up to the face of the modern music consumer, and reveal to us our (musical) identities? Does the algorithm hold the answers behind the creative force that is modern music? Or hold an opinion about our tendency to attribute individuality to listening habits? Can Big Data explain how our seemingly arbitrary (though deeply important) music choices play into the broader socio-economic and geo-political structures?

For starters, what is a music identity?

I) ‘’Uniquely Yours’ — Which way to my tribe?

On average, music preferences are the most common conversation starter among strangers. Our musical tastes are a permanent fixture of our identity, and its formation has grown to represent a near universal rite of passage for modern youth. A trip to the furthest reaches of Brazilian shanty towns may reveal a group of kids holding onto real-sized posters of Justin Bieber. Music journalists will have you believe that, somehow, the choice of our music idols offers a window to our soul.

How well does this narrative stack up against the latest big data insights?

A new study of a remote Amazonian tribe debunks the idea that our brain holds the answer to our musical preferences, and instead, attributes our musical taste to cultural origin. The team at MIT draws a clear distinction between the propensity for certain chords (C and G) evangelised in the Western pop music and the preference for less-consonant sounds prevalent in non-Western cultures. In another blow to our solipsistic inclinations, sociologists discovered that our collective tendency, even as babies, is to favour the music and sounds we are most familiar with.

Globally, we already know that around half our income is determined by our location, or a place of birth for most people. Whether we are likely to protest this fact by going to a punk or a reggae concert seems to be a function of our place of birth as well.

II) ’For being in your own world’ — It’s not all Rock’n’Roll

Have you ever experienced a eureka moment prompted by your friend’s confession of their emo/metal/grunge roots?

Findings from the latest machine learning study run by the Spotify team may offer some clues into this phenomenon. Spotify’s data wizards have explored the connection between the Big Five personality traits, on the one hand, and habitual listening behaviours and musical preferences on the other, and the breadth of insights was nothing short of a revelation.

Enabled by a rich sample consisting of 17.6 million songs, and 662,000 hours of music listened to by 5,808 Spotify users spanning a 3-month period, the study concluded that musical preferences can indeed predict the personality traits with moderate to high accuracy.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, mood and genre information have most strongly correlated to personality traits. One of the constraints of this study is that the respondents had to self-assess their personality, and it is unclear to what extent our perception of our own personality matches reality.

Be that as it may, an average music listener may still be intrigued by the study’s findings, although hardly very surprised.

Listening to soul or ‘lively’ music (e.g., ‘Let The Good Times Roll’ by Ray Charles) correlated with emotional stability. Listening to blues or ‘brooding’ music (e.g., ‘Karma Police’ by Radiohead) had an opposite effect. Jazz or country music listeners fared higher on the ‘agreeable’ personality trait, compared to listeners of death metal or ‘aggressive’ music (e.g., ‘Last Resort’ by Papa Roach).

In a similar vein, fans of R&B and Latin music scored highly on ‘Agreeableness’, as opposed to lovers of ‘regional music (Japan)’, gothic and rock. Modern and alt rock fans fell on the low end of the ‘emotional stability’ spectrum, in contrast to listeners of blues, old country and soul.

The study also revealed what’s behind our listening habits: the participants predominantly listened to Spotify either to regulate emotion or match goal-oriented behaviour. Anthropologists might see this as an indictment of our culture’s obsession with productivity and the pursuit of happiness.

How applicable are these findings? Since the dataset was limited to a small group of US Spotify users, it will be difficult to extrapolate more globally, a slight reassurance for all the rock lovers out there (myself included) slightly alarmed by the stats. However, further studies abound exploring a universal link between musical preferences and personality.

III) ‘Time Capsule’ — What happens in high school, stays etched in our psyche for eternity?

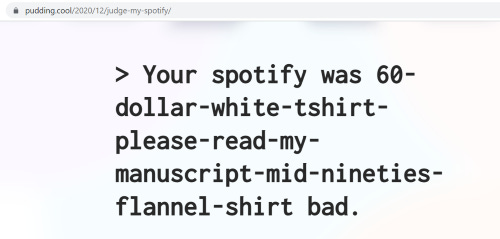

When an increasingly popular and equally sassy AI bot behind the ‘How Bad is Your Spotify’ programme took over the Twittersphere, the most common insult launched at my friend group equated to ‘Your jam hasn’t changed since the Obama era.’

As hurtful as it may be to admit, we can anecdotally appreciate that most grown-ups struggle to outgrow the music that captivated them in their youth. A New York Times analysis can corroborate this theory using Spotify data. The songs we listened to as teens determine our musical taste as adults, the study suggests.

Across the Western world, the data revealed an exact age at which we are most likely to discover and establish our favourite song. This number is as low as 13 years for women, and 14 for men. Coincidentally, women were found to be comparatively more susceptible to childhood influences. The formative years that shaped our musical taste, however, were linked to the end of puberty.

According to the author of the study, these numbers conceal a grim reality: there is no escaping the shackles of high school. Ever.

IV) ‘Discover weekly’ — Are we complicit in the corporatisation of music?

Millennials like myself can feel nostalgic about the ancient modes of music discovery. From frequenting the local record store and being condescend/educated by the music buff (see ‘High Fidelity’) to scouring the pages of music magazines in hope of stumbling upon a gem.

Much has been written about the supremacy of Spotify as a streaming service, in great part owing to its music discovery algorithms, and its recommendation engine built on collaborative filtering model, NLP and audio models.

The same algorithm is ‘instructed’ to keep the user’s finger as far away from the skip button as possible by recognising and including played songs in future playlists. The service is rooted in familiarity, and its playlists centred around emotions, moods and activities as opposed to individual artists, albums, or genres.

Spotify detractors rail against the playlistification trend and its focus on mood-themed playlists proclaiming them to be ‘easy listening’. In an insidious fashion, they claim, Spotify are making music ‘less interesting, less diverse and more corporate’ and instead offering ‘ background noise made from stock sounds.’ By relying on the platform to help us find more of the same music, the argument goes, we are choosing to elevate boring music, and as a result, turning into bores ourselves.

Instead, we are advised to take a more active role in exploring alternative channels for music discovery. This can be via traditional routes of seeking advice from family, friends and favourite artists or by heading to a local public space armed with our ears and a curious mind.

V) ‘Build your own sound’- The mechanics of music making, is it all just 0s and 1s?

In a relatively recent interview for the New York Times, the artist Grimes predicted a future in which AI will be able to generate ‘superhumanly talented artists’, akin to ‘ David Bowie times a million.’ In other words, Grimes made a bold guess as to what the future holds in store for musicians and music itself.

Across the artistic world, the advances in machine learning, including the onset of large language models, have been challenging the idea of the creative process and authorial agency. Writer Meghan O’Gieblyn raises a captivating question about authenticity and originality in areas such as writing and composition. Specifically, she wonders about the degree to which her own writing relies on a reconstruction of familiar tropes and structures while drawing on the world’s ancient myths, much in the way in which programmers used to play with combinations of 0s and 1s.

Spotify has followed mathematical processes in separating a song into instrument layers, and anatomising its structure and rhythm. Its personalised recommendation model learns based on features such as acoustics, genre, danceability, the wordiness of lyrics and the way the popular features interrelate.

For artists caught in this trend, the choice seems obvious enough: join the revolution or get left behind. Music scholars worry that the subordination of music to data science will lead to a new breed of musicians and producers — those who think and act as data curators: apt at optimising the content, code and metadata all to appease the algorithm.

‘Everything I know about music‘ - Where to next?

Spotify as a Musical Oracle experiment has demonstrated the breadth and depth of musical data available for cultural and anthropological mining. Of the many ways in which music has been known to enhance our lives, we now know that its digital trail can also help improve our self-awareness.

By downloading and analysing our personal Spotify history or taking a musical questionnaire, we might become more aware of our personality traits and the (un)conscious ways in which we rely on and ‘use’ music. As if in a therapy session, reminiscing about our favourite tunes may take us on a trip down memory lane to re-encounter our teenage selves. Once there, it might be rewarding to dust off the old family tree and appreciate how our place of origin influenced out music taste, amongst other things.

We can also decide to be more intentional about the journey of our musical discovery. To celebrate the musical identities we share with perfect strangers and support social entrepreneurs keen to overcome social divisions via the power of music.

My personal take away from this exercise is much more mundane — instead of fussing and fuming about the state of my playlists, I’ve decided to rein in my cyborg-ish tendencies and approach my musical habits in a more human fashion — curiously and by allowing for a large margin of error.